Track Your Sleep with Our Sleep/Wake Diary

Keeping a sleep/wake diary can provide valuable insight into patterns that affect the quality and consistency of your rest. By […]

Read complete blog >>

Couples facing separation must cut their legal and financial ties and grow out of their emotional ties. Of these, the emotional ties, the attachment between partners, is often the most difficult to end. Yet it is frequently overlooked by the couple and by those supporting them. The lingering attachment, however, is likely to influence negotiations over child arrangements and financial agreements.

John Bowlby was the first to propose that humans are biologically predisposed to form attachments. An infant establishes the first bond with their caregiver. Throughout life, we continue to seek relationships that provide connection and care. Attachment and healthy dependency across the lifespan are vital to our well-being. Receiving comfort and support from a loved one in times of distress fosters safety and security. It also protects us from depression, helplessness, and a sense of meaninglessness. In couples therapy, one of the central goals is to repair and strengthen the attachment bond between partners.

Adult attachment remains powerful even as a relationship approaches its end. Partners often oscillate between intense positive and negative feelings toward one another. Even in predominantly unhappy relationships, the couple has an attachment bond that takes time to unravel. The anticipated loss of this bond can threaten both partners’ emotional security. This bond once gave both partners a sense of identity and agency, helping them feel safer and more in control in the world. When this is lost, strong emotions are inevitable when a relationship ends.

Crabtree and Harris interviewed individuals experiencing ambiguous separation, where there was no clear intent to divorce because one or both spouses were uncertain about remaining married. Most participants reported benefits such as reduced conflict and opportunities for personal growth. However, none viewed the situation as sustainable, and many felt their lives were on hold. They also described struggles with blurred relational boundaries, social isolation, and loneliness. A key theme that emerged was that separation did not provide greater clarity about the future of the marriage.

Research on ambiguous separation shows that couples do not always transition smoothly from attachment to letting go. Most couples in crisis will, at some stage, feel ambivalence about their relationship. However, many therapists, both individual and couples therapists, find this ambivalence uncomfortable and may inadvertently interfere with their clients’ decision-making. Unfortunately, some couples therapists also erroneously assume that once one partner expresses a desire to end the relationship, the decision is final and believe that couples therapy should be terminated. Ending therapy at this stage is premature and withdraws vital support at a time when couples often need it most.

Similarly, many people often assume that once a couple begins the legal separation or divorce process, both partners wish to end the relationship and have little interest in reconciliation, especially when they appear acrimonious. Expressions of anger and resentment, or cold indifference, may suggest that the connection between the couple is weak. However, beneath the surface, often unconsciously, many individuals are protesting the loss of the attachment bond or trying to preserve it in the best way they know. Paradoxically, this protest can have the opposite effect, driving their partner even further away. In reality, separating couples’ relationships and hopes for the future are nuanced and multifaceted. Clarity about the best path forward may take considerable time to emerge.

This ambivalence was highlighted in a study of over 2,000 divorcing parents. The researchers found that approximately 25% of the participants believed their marriage could still be saved. Around 30% expressed interest in reconciliation, and in 10% of cases, both spouses did. Men were generally more inclined toward reconciliation than women. Unsurprisingly, spouses who had not initiated the divorce process were more likely to express interest in reconciliation than those who had filed for divorce.

Separation and divorce are life-changing events, often deeply painful and destabilising experiences for both the couple and their children. Couples on the brink face only difficult options: doing nothing, ending the relationship, or engaging in therapy. These options are all challenging in different ways. Whatever path they choose, they should make their decision with confidence that it is the most constructive among the difficult options available.

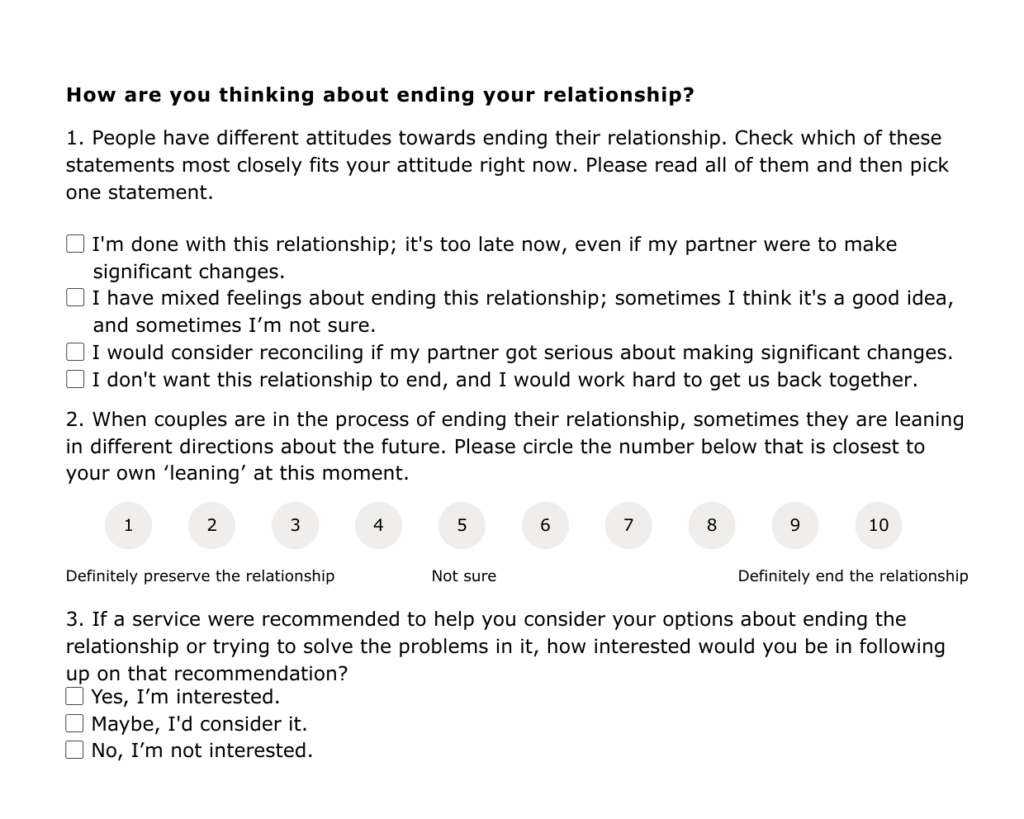

Doherty, Harris, and Didericksen developed a practical, time-efficient protocol to help divorce lawyers and mediators assess divorce ambivalence and explore reconciliation with their clients. Designed for use during the intake process, the tool is straightforward to administer. It provides family mediators with a practical tool to quickly assess each partner's level of ambivalence and decide whether the couple could benefit from specialist support.

The protocol consists of a participant self-assessment and a brief discussion during the MIAM, after which the mediator can make a referral to discernment counselling. This short-term intervention helps couples gain greater clarity and confidence in deciding the future of their relationship.

The self-assessment is a brief questionnaire that can be incorporated into the mediation intake forms, which participants complete before MIAM (see Figure 1).

During the MIAM, the mediator should explore the participant’s position on separation or divorce, especially when signs of ambivalence emerge. For example, the mediator might say: “I see that you checked [participant's answer to question 1]. Could you tell me more about why you chose that response?”

The mediator should listen to both hard and soft problems in the relationship. Hard problems are the ‘three A’s’: addictions, abuse and affairs. When these issues are ongoing and unaddressed, they create conditions in which a healthy relationship cannot function. The partner engaging in such harmful behaviours must take responsibility and seek help, regardless of whether the relationship continues. Importantly, they should not make their desire to change conditional on their partner staying in the relationship.

Soft problems, by contrast, are the shared responsibility of both partners. These typically arise from relational dynamics and often unconscious patterns rooted in our past. Issues such as loneliness, lack of intimacy, or frequent conflict may cause significant pain. However, they are less destructive to the long-term health of the relationship than hard problems.

The mediator may also ask how the participant thinks their partner would have answered the attitude questions, and whether their stances align or diverge. It can be helpful to inquire whether the couple has previously attempted to address their difficulties, for example, through couples therapy, and whether they gained anything from it. Such a discussion offers valuable insight into the couple’s motivation, the therapist’s competence, and the duration of prior treatment.

Training note: The scope of this article does not allow for a deeper exploration of the divorce ambivalence discussion. However, free training is available through The Doherty Relationship Institute for divorce lawyers and mediators to manage this brief assessment with confidence.

Suppose either or both partners are ambivalent about separation and divorce, the mediator can provide information about discernment counselling. When ambivalence persists, discernment counselling offers a structured framework for mixed-agenda couples, where one partner is leaning out of the relationship and considering separation or divorce, while the other is leaning in and wishes to continue. As Doherty and Harris explain, discernment counselling “…creates a holding environment for the couple to develop clarity and confidence in deciding on the next step for their relationship, whether it is divorce or a shared commitment to couples therapy to repair the relationship.” (p. 10)

The goal of discernment counselling is to provide couples with clarity and confidence in their decision-making. The process slows the pace, giving the couple time to reflect on their options carefully. Sessions include both joint discussions and individual conversations with the therapist. The individual time allows each partner to deepen their understanding of their role in the relational dynamic and to gain clearer insight into their future choices.

It is important to note that discernment counselling is not couples therapy. Couples therapy works only if both partners are motivated to work on improving the relationship, with the focus on healing past hurts and strengthening the attachment bond. In contrast, in discernment counselling, the therapist does not aim to facilitate repair or reconciliation. Instead, its purpose is to help partners clarify their current stance and decide on the next step. The discernment counsellor will invite couples to reflect on three possible paths:

Discernment sessions are scheduled one at a time; the number of sessions typically ranges from one to five. You can find an example of a detailed description of discernment counselling written for mixed-agenda couples here.

In a research study on the outcomes of 100 consecutive discernment counselling cases, 12% of the couples chose Path 1 . 41% of the couples chose Path 2, and the remaining 47% decided to engage with couples therapy. At follow-up 12-28 months later, over 60% of the couples who had discenrment counselling still moved ahead with divorce. The research indicates that these couples are in a state of flux, shifting positions.

A discernment counsellor does not see separation or divorce as a failure. Instead, discernment counselling is unsuccessful if a couple does not gain greater clarity about their future and if neither partner has learned how they have contributed to the relationship’s difficulties. The ultimate aim is for couples to accept the outcome, whether separation or renewed commitment, and to carry forward the lessons learned so they do not repeat past mistakes in their current or future relationships.

Doherty and Harris suggest that discernment counselling has the potential to improve post-divorce healing for all parties involved: “Although we do not yet have data to back up our belief, we think that discernment counseling can lead to better healing after divorce for all parties involved. This kind of deliberate decision-making process can lead to better choices about both ending the marriage and moving ahead as parents. It can diminish the kind of anxious attachment that keeps ex-spouses preoccupied with one another” (pp. 122–123).

At present, empirical evidence to support this belief is limited. Emerson, Harris, and Ahmed found that couples who participated in discernment counselling before divorce reported several benefits. They felt more able to accept the decision to divorce, had engaged in more honest conversations with their spouse, and had gained insight into relational patterns they could work on in the future. Participants also indicated that the structured process reduced their ambivalence, increased their readiness for the legal proceedings, and supported more constructive post-divorce co-parenting.

Although these findings are promising, the study was based on a small sample, and further research is needed before we can draw firm conclusions on the benefits of the discernment process. Compared with Crabtree and Harris’s study on ambiguous separation, however, it appears that separation alone neither brings clarity about the future of a marriage nor helps grow out of the attachment bond. The strength of discernment counselling may lie in helping couples begin to let go of the emotional ties between them.

Given the number of mixed-agenda couples seeking separation or divorce, addressing ambivalence first through discernment counselling may reduce the likelihood of post-divorce regret or the sense that not enough was done to try to save the relationship. When individuals feel included in the decision-making process, they are less likely to experience resentment, as they retain a sense of control over the outcome. In clinical practice, separation or divorce reached as a joint decision, rather than imposed unilaterally, tends to be easier for couples to accept and live with. Conversely, when one partner feels forced into a process they do not want, they are less likely to commit to a constructive, non-adversarial approach. This reluctance can foster resentment, heighten conflict, and cause delays in mediation.

Evidence suggests that up to 30% of individuals seeking separation or divorce feel ambivalent about the future of their relationship. Emerging findings also indicate that discernment counselling can help reduce ambivalence and conflict while fostering greater cooperation after a decision to divorce.

The divorce ambivalence protocol offers mediators a time-efficient way to address ambivalence constructively. Doing so not only supports better decision-making for couples but may also reduce conflict, improve cooperation, and strengthen mediation outcomes.

Figure 1. Divorce and separation ambivalence intake questions. (adapted from Doherty, Harris and Didericksen’s self-assessment.)

Is your relationship in a crisis? Find your discernment counsellor and couples therapist on Hoopfull.

Articles on www.hoopfull.com may feature advice and are for informational purposes only. It is not intended to be a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment from a trained professional. In an emergency, please seek help from your local medical or law enforcement services.

Keep up to date with the Hoopfull community.

Keeping a sleep/wake diary can provide valuable insight into patterns that affect the quality and consistency of your rest. By […]

Read complete blog >>

Attachment in adult relationships Couples facing separation must cut their legal and financial ties and grow out of their emotional […]

Read complete blog >>

We spend years in school learning math, biology, and history, but very few of us are ever taught the actual […]

Read complete blog >>